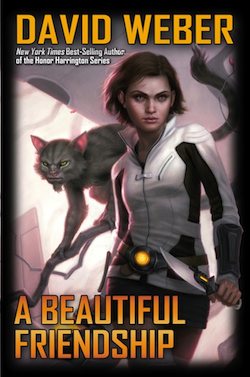

From David Weber, author of the Honor Harrington books, comes the first YA novel is his new Stephanie Harrington series, A Beautiful Friendship (out on October 4 from Baen Books).

Stephanie Harrington always expected to be a forest ranger on her homeworld of Meyerdahl . . . until her parents relocated to the frontier planet of Sphinx in the far distant Star Kingdom of Manticore. It should have been the perfect new home —- a virgin wilderness full of new species of every sort, just waiting to be discovered. But Sphinx is a far more dangerous place than ultra-civilized Meyerdahl, and Stephanie’s explorations come to a sudden halt when her parents lay down the law: no trips into the bush without adult supervision!

Yet Stephanie is a young woman determined to make discoveries, and the biggest one of all awaits her: an intelligent alien species.

The forest-dwelling treecats are small, cute, smart, and have a pronounced taste for celery. And they are also very, very deadly when they or their friends are threatened . . . as Stephanie discovers when she comes face-to-face with Sphinx’s most lethal predator after a hang-gliding accident.

?1

“I mean it, Stephanie!” Richard Harrington said. “I don’t want you wandering off into those woods again without me or your mom along. Is that clear?”

“Oh, Daaaddy—!” Stephanie began, only to close her mouth sharply when her father folded his arms. Then the toe of his right foot started tapping lightly, and her heart sank. This wasn’t going well at all, and she resented that reflection on her . . . negotiating skills almost as much as she resented the restriction she was trying to avoid. She was almost twelve T-years old, smart, an only child, and a daughter. That gave her certain advantages, and she’d become an expert at wrapping her father around her finger almost as soon as she could talk. Unfortunately, her mother had always been a tougher customer . . . and even her father was unscrupulously willing to abandon his proper pliancy when he decided the situation justified it.

Like now.

“We’re not going to discuss this further,” he said with ominous calm. “Just because you haven’t seen any hexapumas or peak bears doesn’t mean they aren’t out there.”

“But I’ve been stuck inside with nothing to do all winter,” she said, easily suppressing a twinge of conscience as she neglected to mention snowball fights, cross-country skiing, sleds, snow tunnels, and certain other diversions. “I want to go outside and see things!”

“I know you do, honey,” her father said more gently, reaching out to tousle her curly brown hair. “But it’s dangerous out there. This isn’t Meyerdahl, you know.” Stephanie closed her eyes and looked martyred, and his expression showed a flash of regret at having let the last sentence slip out. “If you really want something to do, why don’t you run into Twin Forks with Mom this afternoon?”

“Because Twin Forks is a complete null, Daddy.”

Exasperation colored Stephanie’s reply, even though she knew it was a tactical error. Even above-average parents like hers got stubborn if you disagreed with them too emphatically, but honestly! Twin Forks might be the closest “town” to the Harrington freehold, but it boasted a total of maybe fifty families, most of whose handful of kids were a total waste of time. None of them were interested in xeno-botany or biosystem hierarchies. In fact, they spent most of their free time trying to catch anything small enough to keep as pets, however much damage they might do to their intended “pets” in the process. Stephanie was pretty sure any effort to enlist those zorks in her explorations would have led to words—or a fist in the eye—in fairly short order. Not, she thought darkly, that she was to blame for the situation. If Dad and Mom hadn’t insisted on dragging her away from Meyerdahl just when she’d been accepted for the junior forestry program, she’d have been on her first internship field trip by now. It wasn’t her fault she wasn’t, and the least they could do to make up for it was let her explore their own property!

“Twin Forks is not a ‘complete null,’” her father said firmly.

“Oh yes it is,” she replied with a curled lip, and Richard Harrington drew a deep breath.

“Look,” he said after a moment, “I know you had to leave all your old friends behind on Meyerdahl. And I know how much you were looking forward to that forestry internship. But Meyerdahl’s been settled for over a thousand T-years, Steph, and Sphinx hasn’t.”

“I know that, Dad,” she replied, trying to make her voice as reasonable as his. That first “Daddy!” had been a mistake. She knew that, and she didn’t plan on repeating it, but his sudden decree that she stay so close to the house had caught her by surprise. “But it’s not like I didn’t have my uni-link with me. I could’ve called for help anytime, and I know enough to climb a tree if something’s trying to eat me! I promise—if anything like that had come along, I’d’ve been sitting on a limb fifteen meters up waiting for you or Mom to home in on my beacon.”

“I know you would have . . . if you’d seen it in time,” her father said in a considerably grimmer tone. “But Sphinx isn’t ‘wired’ the way Meyerdahl was, and we still don’t know nearly enough about what’s out there. We won’t know for decades yet, and all the unilinks in the world might not get an air car there fast enough if you did run into a hexapuma or a peak bear.”

Stephanie started to reply, then stopped. He had a point, she admitted grudgingly. Not that she meant to give up without a fight! But one of the five-meter-long hexapumas would be enough to ruin anyone’s day, and peak bears weren’t a lot better. And he was right about how little humanity knew about what was really out there in the Sphinx brush. But that was the whole point, the whole reason she wanted to be out there in the first place!

“Listen, Steph,” her father said finally. “I know Twin Forks isn’t much compared to Hollister, but it’s the best I can offer. And you know it’s going to grow. They’re even talking about putting in their own shuttle pad next spring!”

Stephanie managed—somehow—not to roll her eyes again. Calling Twin Forks “not much” compared to the city of Hollister was like saying it snowed “a little” on Sphinx. And given the long, dragging, endless year of this stupid planet, she’d almost be seventeen T-years old by the time “next spring” got here! She hadn’t quite been ten and a half when they arrived…just in time for it to start snowing. And it hadn’t stopped snowing for the next fifteen T-months!

“Sorry,” her father said quietly, as if he’d read her thoughts. “I’m sorry Twin Forks isn’t exciting, and I’m sorry you didn’t want to leave Meyerdahl. And I’m sorry I can’t let you wander around on your own. But that’s the way it is, honey. And”—he gazed sternly into her brown eyes—“I want your word you’ll do what your mom and I tell you on this one.”

???

Stephanie squelched glumly across the mud to the steep-roofed gazebo. Everything on Sphinx had a steep roof, and she allowed herself a deep, heartfelt groan as she plunked herself down on the gazebo steps and contemplated the reason that was true.

It was the snow. Even here, close to Sphinx’s equator, annual snowfall was measured in meters—lots of meters, she thought moodily—and houses needed steep roofs to shed all of that frozen water, especially on a planet whose gravity was over a third higher than Old Earth’s. Not that Stephanie had ever seen Old Earth . . . or any world which wasn’t classified as “heavy-grav” by the rest of humanity.

She sighed again, with an edge of wistful misery, and wished her great-great-great-great-whatever grandparents hadn’t volunteered for the Meyerdahl First Wave. Her parents had sat her down to explain what that meant shortly after her eighth birthday. She’d already heard the word “genie,” though she hadn’t realized that, technically at least, it applied to her, but she’d only started her classroom studies four T-years before. Her history courses hadn’t gotten to Old Earth’s Final War yet, so she’d had no way to know why some people still reacted so violently to any notion of modifications to the human genotype . . . or why they considered “genie” one of the dirtiest words in Standard English.

Now she knew, though she still thought anyone who felt that way was silly. Of course the bio-weapons and “super soldiers” whipped up for the Final War had been horrible. But that had all happened over five hundred T-years ago, and it hadn’t had a thing to do with people like the Meyerdahl or Quelhollow first waves. She supposed it was a good thing the original Manticoran settlers had left Sol before the Final War. Their old-fashioned cryo ships had taken long enough to make the trip for them to miss the entire thing . . . and the prejudices that went with it.

Not that there was anything much to draw anyone’s attention to the changes the geneticists had whipped up for Meyerdahl’s colonists. Mass for mass, Stephanie’s muscle tissue was about twenty-five percent more efficient than that of “pure strain” humans, and her metabolism ran about twenty percent faster to fuel those muscles. There were a few minor changes to her respiratory and circulatory systems (to let her handle a broader range of atmospheric pressures without the nanotech pure-strainers used), and some skeletal reinforcement to cope with the muscles, as well. And the modifications had been designed to be dominant, so that all her descendants would have them. But her kind of genie was perfectly inter-fertile with pure-strainers, and as far as she could see all the changes put together were no big deal. They just meant that because she and her parents needed less muscle mass for a given strength they were ideally suited to colonize high-gravity planets without turning all stumpy and bulgy-muscled. Still, when she’d gotten around to studying the Final War and some of the antigenie movements, she’d decided Dad and Mom might have had a point in warning her not to go around telling strangers about it. Aside from that, she seldom thought about it one way or the other . . . except to reflect somewhat bitterly that if they hadn’t been genies the heavy gravities of the Manticore Binary System’s habitable planets might have kept her parents from deciding they simply had to drag her off to the boonies like this.

She chewed her lower lip and leaned back, letting her eyes roam over the isolated clearing in which she’d been marooned by their decision. The tall green roof of the main house was a cheerful splash of color against the still-bare picketwood and crown oaks which surrounded it. But she wasn’t in the mood to be cheerful, and it took very little effort to decide green was a stupid color for a roof. Something dark and drab—brown, maybe, or maybe even black—would’ve suited her much better. And while she was on the subject of inappropriate building materials, why couldn’t they have used something more colorful than natural gray stone? She knew it had been the cheapest way to do it, but getting enough insulating capacity to face a Sphinx winter out of natural rock required walls over a meter thick. It was like living in a dungeon, she thought . . . then paused to savor the simile. It fitted her present mood perfectly, and she stored it away for future use.

She considered it a moment longer, then shook herself and gazed at the trees beyond the house and its attached greenhouses with a yearning that was almost a physical pain. Some kids knew they wanted to be spacers or scientists by the time they could pronounce the words, but Stephanie didn’t want stars. She wanted . . . green. She wanted to go places no one had ever been yet—not through hyper-space, but on a warm, living, breathing planet. She wanted waterfalls and mountains, trees and animals who’d never heard of zoos. And she wanted to be the first to see them, to study them, understand them, protect them. . . .

Maybe it was because of her parents, she mused, forgetting to resent her father’s restrictions for the moment. Richard Harrington held degrees in both Terran and xeno-veterinary medicine. They made him far more valuable to a frontier world like Sphinx than he’d ever been back home, but he’d occasionally been called upon by Meyerdahl’s Forestry Service. That had brought Stephanie into far closer contact with her birth world’s animal kingdom than most people her age ever had the chance to come. And her mother’s background as a plant geneticist—another of those specialties new worlds found so necessary—had helped her appreciate the beautiful intricacies of Meyerdahl’s flora, as well.

Only then they’d brought her way out here and dumped her on Sphinx.

Stephanie grimaced in fresh disgust. Part of her had deeply resented the thought of leaving Meyerdahl, but another part had been delighted. However much she might have longed for a Wildlife Management Service career, the thought of starships and interstellar voyages had been exciting. And so had the thought of emigrating on a sort of rescue mission to help save a colony which had been almost wiped out by plague. (Although, she admitted, that part would have been much less exciting if the doctors hadn’t found a cure for the plague in question.) Best of all, her parents’ specialties meant the Star Kingdom had agreed to pay the cost of their transportation, which—coupled with their savings—had let them buy a huge piece of land all their own. The Harrington freehold was a rough rectangle thrown across the steep slopes of the Copperwall Mountains to overlook the Tannerman Ocean, and it measured twenty-five kilometers on a side. Not the twenty-five meters of their lot’s frontage in Hollister, but twenty-five kilometers, which made it as big as the entire city had been back home! And it backed up against an area already designated as a major nature preserve, as well.

But there were a few things Stephanie hadn’t considered in her delight. Like the fact that their freehold was almost a thousand kilometers from anything that could reasonably be called a city. Much as she loved wilderness, she wasn’t used to being that far from civilization, and the distances between settlements meant her father had to spend an awful lot of time in the air just getting from patient to patient.

At least the planetary data net let her keep up with her schooling and enjoy some simple pleasures—in fact, she was first in her class (again), despite the move, and she stood sixteenth in the current planetary junior chess competition, as well. Of course, that didn’t mean as much here as it would have on Meyerdahl, given how much smaller the population (and pool of competitors) was. Still, it had kept her from developing a truly terminal case of what her mother called “cabin fever,” and she enjoyed her trips to town (when she wasn’t using Twin Forks’ dinkiness in negotiations with her parents). But none of the few kids her age in Twin Forks were in the accelerated curriculum, which meant they weren’t in any of her classes, and she hadn’t gotten to know them on-line the way she’d known all her friends back on Meyerdahl. They probably weren’t all complete nulls, but she didn’t know them. Besides, she admitted, her “peer group interpersonal skills” (as the counselors liked to put it) weren’t her strong suit. She knew she got frustrated quickly—too quickly, often enough—with people who couldn’t keep up with her in an argument or who insisted on doing stupid things, and she knew she had a hot temper. Her mom said that sometimes accompanied the Meyerdahl modifications, and Stephanie tried to sit on it when it got out of hand. She really did try, yet more than one “interpersonal interaction” with another member of her “peer group” had ended with bloody noses or blackened eyes.

So, no, she hadn’t made any friends among Twin Forks’ younger population. Not yet, anyway, and the settlement itself was totally lacking in all the amenities of a city of almost three million people, like Hollister.

Yet Stephanie could have lived with all of that if it hadn’t been for two other things: snow and hexapumas.

She dug a booted toe into the squishy mud beyond the gazebo’s bottom step and scowled. Daddy had warned her they’d be arriving just before winter, and she’d thought she knew what that meant. But “winter” had an entirely different meaning on Sphinx. Snow had been an exciting rarity on warm, mild Meyerdahl, but a Sphinxian winter lasted almost sixteen T-months. That was over a tenth of her entire life, and she’d become well and truly sick of snow. Dad could say whatever he liked about how other seasons would be just as long. Stephanie believed him. She even understood (intellectually) that she had the better part of four full T-years before the snow returned. But she hadn’t experienced it yet, and all she had right now was mud. Lots and lots and lots of mud, and the bare beginning of buds on the deciduous trees. And boredom.

And, she reminded herself with a scowl, she also had the promise not to do anything about that boredom which her father had extracted from her. She supposed she should be glad he and Mom worried about her. But it was so . . . so underhanded of him to make her promise. It was like making Stephanie her own jailer, and he knew it!

She sighed again, rose, shoved her fists into her jacket pockets, and headed for her mother’s office. Marjorie Harrington’s services had become much sought after in the seventeen T-months she’d been on Sphinx, but unlike her husband, she seldom had to go to her clients. On the rare occasions when she required physical specimens rather than simple electronic data, they could be delivered to her small but efficient lab and supporting green houses here on the freehold as easily as to any other location. Stephanie doubted she could get her mom to help her change Dad’s mind about grounding her, but she could try. And at least she might get a little understanding out of her.

???

Dr. Marjorie Harrington stood by the window and smiled sympathetically as she watched Stephanie trudge toward the house. Dr. Harrington knew where her daughter was headed . . . and what she meant to do when she got there. In a general way, she disapproved of Stephanie’s attempts to enlist one parent against the other when edicts were laid down, but one thing about Stephanie: however much she might resent a restriction or maneuver to get it lifted, she always honored it once she’d given her word to do so.

Which didn’t mean she’d enjoy it, and Marjorie’s smile faded as she contemplated her daughter’s disappointment. And the fact that she and Richard had no choice but to restrict Stephanie didn’t make it fair, either.

I really need to take some time away from the terminal, she reflected. There’s no way I could possibly spend as many hours in the woods as Stephanie wants to. There aren’t that many hours in even a Sphinxian day! But I ought to be able to at least provide her with an adult escort often enough for her habit to get a minimum fix.

Her thoughts paused and then she smiled again as another thought occurred to her.

No, we can’t let Steph rummage around in the woods by herself, but there might just be another way to distract her. After all, she’s got that problem-solver streak—the kind of mind that prints out hard copies of the Yawata Crossing Times crossword so she can work them in ink instead of electronically. So with just a little prompting . . .

Marjorie let her chair slip upright and drew a sheaf of hard copy closer as she heard boots moving down the hall towards her office. She uncapped her stylus and bent over the neatly printed sheets with a studious expression just as Stephanie knocked on the frame of the open door.

“Mom?” Dr. Harrington allowed herself one more sympathetic smile at the put-upon pensiveness of Stephanie’s tone, then banished the expression and looked up from her paperwork.

“Come in, Steph,” she invited, and leaned back in her chair once more.

“Can I talk to you a minute?” Stephanie asked, and Marjorie nodded.

“Of course you can, honey,” she said. “What’s on your mind?”

?2

Climbs quickly scurries up the nearest net-wood trunk, then paused at the first cross-branch to clean his sticky true-hands and hand-feet with fastidious care.

He hated crossing between trees now that the cold days were passing into those of mud. Not that he was particularly fond of snow, either, he admitted with a bleek of laughter, but at least it melted out of his fur—eventually—instead of forming gluey clots that dried hard as rock. Still, there were compensations to warming weather, and he sniffed appreciatively at the breeze that rustled the furled buds just beginning to fringe the all-but-bare branches. Under most circumstances, he would have climbed all the way to the top to luxuriate in the wind fingers ruffling his coat, but he had other things on his mind today.

He finished grooming himself, then rose on his rear legs in the angle of the cross-branch and trunk to scan his surroundings with sharp green eyes. None of the two-legs were in sight, but that meant little; two-legs were full of surprises. Climbs Quickly’s own Bright Water Clan had seen little of them until lately, but other clans had observed them for twelve full turnings of the seasons, and it was obvious they had tricks the People had never mastered. Among those was some way to keep watch from far away—so far, indeed, that the People could neither hear nor taste them, much less see them. Yet Climbs Quickly detected no sign that he was being watched, and he flowed smoothly to the adjacent trunk. Now that he was into the last cluster of net-wood, the pattern of its linked branches would at least let him keep his true-feet and hand-feet clear of the muck as he followed the line of cross-branches deeper into the clearing.

He slowed as he reached the final cross-branch, then stopped. He sat for long, still moments, cream and gray coat blending into invisibility against trunks and branches veiled in a fine spray of tight green buds, motionless but for a single true-hand which groomed his whiskers reflexively. He listened carefully, with ears and thoughts alike, and those ears pricked as he tasted the faint mind-glow that indicated the presence of two-legs. It wasn’t the clear, bright communication it would have been from one of People, for the two-legs appeared to be mind-blind, yet there was something . . . nice about it. Which was odd, for whatever else they were, the two-legs were very unlike the People. That much had been obvious from the very beginning.

<What are you listening for, Climbs Quickly?> a mind-voice asked, and he looked back over his shoulder.

Shadow Hider was well named, for more than one reason, he thought. The other scout was all but invisible against the net-wood bark, even to Climbs Quickly, who knew exactly where he was from his mind-glow. Climbs Quickly had no fear that Shadow Hider would betray their presence to the two-legs, but that was unlikely to make him any more pleasant as a companion.

<The two-leg mind-glow,> he replied to the question, and tasted Shadow Hider’s flicker of irritation at the tone of his own mindvoice. He’d made no attempt to hide the exaggerated patience of that tone, since Shadow Hider would have tasted the emotions behind it just as clearly.

<Why?> Shadow Hider asked bluntly. <We already know they are as mind-blind as the burrow runners or the bark-chewers, Climbs Quickly.>

Shadow Hider’s disdain for any creatures who were so completely deaf and dumb was obvious in his mind-glow, and Climbs Quickly suppressed a desire to cross back over to the junior scout’s position and cuff him sharply across the nose. He reminded himself that Shadow Hider was far younger than he, and that those who knew the least often thought they knew the most, but that made the other scout no less frustrating. And, of course, the People’s ability to taste one another’s emotions meant Shadow Hider knew exactly how Climbs Quickly felt, which made things no better.

<Yes, they appear to be mind-blind, Shadow Hider,> he replied after a moment. <But do not make the mistake of thinking that means they are no more clever than a burrow runner! Can you do the things the People have seen the two-legs do? Can you fly? Can you gnaw down an entire golden-leaf tree in an afternoon? Because if you cannot, perhaps you should remember that the two-legs can . . . which is why we have been sent to keep watch on them in the first place!>

He tasted Shadow Hider’s flare of anger clearly, but at least the younger scout was wise enough not to snap back at him. Which was the first wise thing Climbs Quickly had seen from him since they’d left Bright Water Clan’s central nest place this morning.

This is Broken Tooth’s idea, Climbs Quickly thought disgustedly. The clan’s senior elder had argued for some time now that Climbs Quickly was becoming too captivated by the two-legs. If it were left up to him, Shadow Hider would have this task, not someone he fears is more interested in what the two-legs are and where they came from—and why—than in simply keeping watch upon them!

Climbs Quickly had been the first scout to discover these twolegs’ presence, and he admitted that he found everything about them fascinating, which was one reason Broken Tooth questioned his fitness to keep continued watch upon them. Clearly the elder believed Climbs Quickly was too fascinated with what he regarded as “his” two-legs to be truly impartial in his observations of them. Fortunately the rest of the clan elders—especially Bright Claw, the clan’s senior hunter, and Short Tail, the senior scout— trusted Climbs Quickly’s judgment and continued to believe he was the better choice to continue keeping watch upon them. In fact, though none of them had actually said so, from the taste of their mind-glows Climbs Quickly felt fairly certain that they agreed the task required someone with far more imagination than Shadow Hider had ever revealed. Unfortunately, it did make sense for more than one of the clan’s scouts to have some experience with it, and Climbs Quickly was willing to admit that another perspective might prove valuable.

Even if it was Shadow Hider’s.

He waited a moment longer, to see if Shadow Hider had something more to say after all, then turned back to the cross-branch and the clearing. The bright ember of Shadow Hider’s anger faded with distance behind Climbs Quickly as he crept stealthily out to the last net-wood trunk, climbed easily to its highest fork, and settled down on the pad of leaves and branches. The cold days’ ravages required a few repairs, but there was no hurry. The pad remained serviceable and reasonably comfortable, and it would be many days yet before the slowly budding leaves could provide the needed materials, anyway.

<Come now!> he called to Shadow Hider, then curled himself neatly to one side of the pad and allowed himself to savor the sun’s gentle warmth.

In a way, he would be unhappy when the leaves did open and bright sunlight could no longer spill through the thin upper branches to caress his fur. His pad would have better concealment, which would undoubtedly make Shadow Hider happier, but if he had his way Shadow Hider wouldn’t be here by that time, anyway.

Claws scraped lightly on bark as Shadow Hider swarmed up the last few People’s lengths of trunk and joined him. The other scout looked around Climbs Quickly’s pad, as if trying to find something with which to take fault. Climbs Quickly tasted his annoyance when he couldn’t, but then Shadow Hider flirted his tail and settled down beside him.

<This is a good scouting post,> the younger scout acknowledged almost grudgingly after a few moments. <You have an even better view than I thought you did, Climbs Quickly. And the two-leg nesting place is larger than I had thought.>

<It is large,> Climbs Quickly agreed, reminding himself that size was one of the hardest things to judge from another scout’s reports. The memory singers could sing that report perfectly, showing another of the People everything the original scout had seen, but for some reason, estimates of size remained difficult to share without some reference point. The only true reference point the two-legs had left in this case, however, was the towering golden-leaf whose massive boughs shaded their nest place, and golden-leaf trees tend to make anything look small.

<Why should they need a nest place so large?> Shadow Hider wondered, and Climbs Quickly flicked his ears.

<I have wondered that myself,> he admitted, <and I have never found an answer that satisfies me. It required great labor by over a dozen two-legs, even with their tools, to build that living place. I watched them for many days, and when they were done, they simply went away. It was over three hands of days before the new two-legs came, and there are only three of them even now.>

<I know that was what you had reported, but now that I have seen how large their nest is it seems even stranger.>

Climbs Quickly gave a soft bleek of amusement at the perplexity in the other scout’s mind-voice, but then that amusement faded.

<Unless I am mistaken, the smallest of the two-legs is only a youngling,> he said. <I cannot be positive, of course, but if that is so, I wonder if perhaps something happened to its littermates. Could that be why their nest seems so vast? If they lost their other younglings to some accident only after they had planned their nest’s size…>

Shadow Hider said nothing, but Climbs Quickly tasted his understanding…and a glow of sympathy for the two-legs’ loss which made Climbs Quickly think somewhat better of him.

<It is strange that they live so apart from one another,> Shadow Hider said after some moments. <Why should a single mated pair and their young build a nest so from any others of their kind? Surely it must deprive them of any chance to communicate with other two-legs! Assuming they do communicate, of course.>

<I think they must communicate in some fashion,> Climbs Quickly replied thoughtfully. <The two-legs who made this clearing and built the nesting place surely had to be able to communicate with one another in order to accomplish so many different tasks so quickly!>

Shadow Hider considered that, recalling the memory song of Climbs Quickly’s first glimpse of the two-legs in question.

The clan had not been too apprehensive when the first flying thing arrived and the two-legs emerged to create the clearing, for the clans whose territories had already been invaded had warned of what to expect. The two-legs could be dangerous, and they kept changing things, but they weren’t like death fangs or snow hunters, who all too often killed randomly or for pleasure, and Climbs Quickly and a handful of other scouts and hunters had watched that first handful of two-legs from the cover of the frost-bright leaves, perched high in the trees. The newcomers had cut down enough net-wood and green-needle trees to satisfy themselves, then spread out carrying strange things—some that glittered or blinked flashing lights, and others that stood on tall, skinny legs—which they moved from place to place and peered through. And then they’d driven stakes of some equally strange non-wood into the ground at intervals. The Bright Water memory singers had sung back through the songs from other clans and decided the things they peered through were tools of some sort. Climbs Quickly couldn’t argue with their conclusion, yet the twoleg tools were as different from the hand axes and knives of the People as the substance of which they were made was unlike the flint, wood, and bone the People used.

All of which explained why the two-legs must be watched most carefully . . . and secretly. Small as the People were, they were quick and clever, and their axes and knives and use of fire let them accomplish things larger but less clever creatures could not. Yet the shortest two-leg stood more than two People-lengths in height. Even if their tools had been no better than the People’s (and Climbs Quickly knew they were much, much better) their greater size would have made them far more effective. And if there was no sign the two-legs intended to threaten the People, there was also no sign they did not, so no doubt it was fortunate mind-blind creatures were so easy to spy upon.

<Very well,> Shadow Hider said finally, his mind-glow grudging, <perhaps they are able to communicate . . . somehow. Yet as you yourself have reported, Climbs Quickly, they truly do appear to be mind-blind.> The younger scout flattened his ears uneasily. <I think that is the thing I find most difficult to understand about them. The thing that makes me . . . anxious about them.>

Climbs Quickly felt a flicker of surprise. That wasn’t the sort of admission—or insight—he normally expected out of Shadow Hider. Yet the other scout had put his claw squarely upon it, for the two-legs were a new and frightening thing in the People’s experience.

Yet they were not entirely new, which only made many of the People more nervous, not less. When the two-legs had first appeared twelve season-turnings back, the memory singers of every clan had sent their songs sweeping far and wide. They’d sought any song of any other clan which might tell them something— anything—about the strange creatures and whence they had come…or at least why.

No one had been able to answer those questions, yet the memory singers of the Blue Mountain Dancing Clan and the Fire Runs Fast Clan had remembered a very old song—one which went back more than twelve twelves of turnings. The song offered no clue to the two-legs’ origins or purpose, but it did tell of the very first time the People had seen two-legs, and how the long-ago scout who’d brought his report back to the singers had seen their egg-shaped silver thing come down out of the sky.

<I have often wished the Blue Mountain Dancing scouts had been a little less cautious when the two-legs first visited us,> Climbs Quickly admitted to Shadow Hider. <Perhaps we might have been able to decide what the two-legs want—or what we should do about them—between then and now, when they have returned.>

<And perhaps all of the People in the world would have been destroyed then,> Shadow Hider replied. <Although,> he added dryly, <at least if that had happened, we would not be wondering what to do about them now.>

Climbs Quickly was torn between a fresh desire to cuff Shadow Hider and a desire to laugh, but once again, he did have a point.

Personally, Climbs Quickly thought those first two-legs had been scouts, as he himself was. Certainly it would have made sense for the two-legs to send scouts ahead; any clan did the same thing when expanding or changing its range. Yet if that was the case, why had the rest of their clan delayed so long before following? And why did the two-legs spread themselves so thinly?

Shadow Hider was scarcely alone in wondering how—or if— the two-legs truly communicated at all. If they did, even Climbs Quickly was forced to admit that it must be in some bizarre fashion completely unlike the way in which the People did. That was one reason many of the watchers believed two-legs were unlike People in all ways, not just their size and shape and tools. It was the ability to taste their fellows’ mind-glows, hear one another’s mind-voices, which made People people, after all. Only unthinking creatures—like the death fangs, or the snow hunters, or those upon whom the People themselves preyed—lived sealed within themselves. So if the two-legs were not only mind-blind, but chose to avoid even their own kind, they could not be people.

But Climbs Quickly disagreed. He couldn’t fully explain why even to himself, yet he was convinced the two-legs were, in fact, people—of a sort, at least. They fascinated him, and he’d listened again and again to the song of the first two-legs and their egg, both in an effort to understand what it was they wanted and because even now that song carried overtones of something he thought he’d tasted from the two-legs he spied upon.

Shadow Hider is wrong, he thought now. Blue Mountain Dancing’s scouts should have been less cautious.

Yet even as he thought that, he knew he was being unreasonable. Perhaps those long-ago scouts might have approached the intruders, but before any of them had decided to do so, a death fang attempted to eat one of the two-legs.

People didn’t like death fangs. The huge creatures looked much like vastly outsized People, but unlike People, they were far from clever. Not that anything their size really needed to be clever. Death fangs were the biggest, strongest, most deadly hunters in all the world. Unlike People, they often killed for the sheer pleasure of it, and they feared nothing that lived . . . except the People. They never passed up the opportunity to eat a single scout or hunter if they happened across one stupid enough to be caught on the ground, but even death fangs avoided the heart of any clan’s range. Individual size meant little when an entire clan swarmed down from the trees to attack.

Yet the death fang who’d attacked one of the two-legs had discovered something new to fear. None of the watching People had ever heard anything like the ear shattering “Craaaack!” from the tubular thing the two-leg carried, but the charging death fang had suddenly somersaulted end-for-end, crashed to the ground, and lain still, with a bloody hole blown clear through it.

Once they got over their immediate shock, the watching scouts had taken a fierce delight in the death fang’s fate. But anything that could kill a death fang with a single bark could certainly do the same thing to one of the People, and so the decision had been made to avoid the two-legs until the watchers learned more about them. Unfortunately, the scouts were still watching from hiding when, after perhaps a quarter-turning, the two-legs dismantled the strange, square living places in which they had dwelt, went back into their egg, and disappeared once more into the sky.

All of that had been long, long ago, and Climbs Quickly deeply regretted that no more had been learned of them before they left.

<I, too, often wish we had learned more when the two-legs first appeared so long ago,> Shadow Hider said, almost as if he had been reading Climbs Quickly’s very thoughts, and not simply the emotions of his mind-glow. <Yet I also think we are fortunate Blue Mountain Dancing’s scouts saw as much as they did, especially the ease with which they slew the death fang. For that matter, we are fortunate the memory singers were able even to recall the memory song from that long-ago time!>

<You are certainly right about that much, Shadow Hider,> Climbs Quickly agreed, although he did not agree with everything the younger scout had just said. In fact, he believed it was most unfortunate that the death fang’s fate had frightened those long-ago People into avoiding closer contact. They were fortunate to retain a memory song from so long ago, however, especially when it was not one of the songs which had been important to the day-to-day lives of the People in all the weary turnings since it had first been sung.

Yet that very song’s account only fueled Climbs Quickly’s frustrated, maddening curiosity about the two-legs. He’d listened again and again to that song, both in an effort to understand what it was they wanted and because even now that song carried overtones of something he thought he had tasted for the two-legs he spied upon.

Unfortunately, the song had been worn smooth by too many singers before Sings Truly first sang it for Bright Water Clan. That often happened to older songs, or those which had been relayed for great distances, and this song was both ancient and from far away. Though its images remained clear and sharp, they had been subtly shaped and shadowed by all the singers who had come before Sings Truly. Climbs Quickly knew what the two-legs of the song had done, but he knew nothing about why they’d done it, and the interplay of so many singers’ minds had blurred any mind-glow the long-ago watchers might have tasted.

Climbs Quickly had shared what he thought he’d picked up from “his” two-legs only with Sings Truly. It was his duty to report to the memory singers, and so he had. But he’d implored Sings Truly to keep his suspicions only in her own song for now, for some of the other scouts would have laughed uproariously at them, and they might well have strengthened Broken Tooth’s suspicion that Climbs Quickly was not the best choice for his present duties. Sings Truly hadn’t laughed, but neither had she rushed to agree with him, and he knew she longed to travel in person to the Blue Mountain Dancing or Fire Runs Fast Clan’s range to receive the original song directly from their senior singers and not relayed over such a vast distance from one singer to another.

But that was out of the question. Singers were the core of any clan, the storehouse of memory and dispensers of wisdom. They were always female, and their loss could not be risked, whatever Sings Truly might want. Unless a clan was fortunate enough to have a surplus of singers, it must protect its potential supply of replacements by denying them more dangerous tasks. Climbs Quickly understood that, but he found its implications a bit harder to live with than the clan’s other scouts and hunters did. There could be disadvantages to being a memory singer’s brother when she chose to sulk over the freedoms her role denied her . . . and allowed him.

He bleeked softly with laughter at that thought.

<What?> Shadow Hider asked.

<Nothing important,> Climbs Quickly replied. <Just a memory of something Sings Truly said to me. She was not happy at the time.>

<I am glad someone finds that humorous,> Shadow Hider said dryly, and Climbs Quickly laughed again.

It was true that his sister had a formidable temper, and the entire clan still recalled the day a much younger Shadow Hider, but little removed from kittenhood, had accidentally dropped a flint knife. It had fallen perhaps a twelve of People’s lengths and embedded itself in a net-wood limb…perhaps a double hand’s width behind Sings Truly’s tail.

It would not have been humorous if it had fallen any closer, of course. Short Tail had lost the last hand width of his tail to a not dissimilar accident, and it could have injured Sings Truly seriously, even killed her. Shadow Hider’s reaction most definitely had been humorous, however. Indeed, he’d received his name for the way he had vanished into the shadows when Sings Truly began her furious scold at the very top of a memory singer’s mind-voice!

<She would not truly have skinned you for a rug for her nesting place, younger brother,> Climbs Quickly said now, feeling unusually fond of the other scout. <And I do not think she will skin me for one, either. Although there are times I feel less certain of that!>

<Personally, I have no desire to find out whether or not you are correct about that,> Shadow Hider replied with feeling.

<A wise scout does not venture into the death fang’s lair to see whether or not it is at home,> Climbs Quickly agreed, stretching out on his belly with a sigh of pleasure. He folded his true-hands under his chin and settled himself for a long wait, and Shadow Hider settled down beside him.

Scouts learned early to be patient. If they needed help with that lesson, there were teachers aplenty—from falls to hungry death fangs—to drive it home. Climbs Quickly had never needed such instruction, which, even more than his relationship to Sings Truly, was why he was second only to Short Tail as Bright Water Clan’s chief scout, despite his own relative youth.

So now he waited, motionless in the warm sunlight, and watched the sharp-topped living place the two-legs had built in the center of the clearing.

A Beautiful Friendship © David Weber 2011